I bought a lovely little computer, a Raspberry Pi 400, and two accessories, a 64 GB Samsung Pro Endurance microSD card to hold the file system and a very cheap Full HD webcam for video calls.

I always wanted a Raspberry computer but assumed the components and cables would take up too much space at my work station.

Recently though I carefully inspected the layout of my desk, the HDMI ports of my HP Pavillon 23cw monitor, and the nearby electrical sockets. Researching the Raspberry Pi 400 convinced me I could set the device on the desk with minimal inconvenience and little space.

This is not a full review but a collection of early impressions and usage notes after working with the device for a week.

Motivations

Although I have possible uses for the Pi 400, one of the reasons why I got it is not technical: the computer has a delightful form factor.

My daily driver, an ASUS Chromebox 3, is a high end desktop system. But the opportunity of using a different device with a nice form factor is a welcome and refreshing context switch that helps productivity and makes things fun. It's like writers spending time at Starbucks to get some work done instead of sitting and typing at their desk at home.

Another reason for getting the Pi 400 is I always loved Linux. Since switching to chromeOS in 2015 I've been thinking of how to set up a Linux box as a secondary computer within the constraints of my work station. The Pi 400 finally enabled this possibility.

Another major consideration that drew me to the Pi 400 is it's a full, native Linux system specifically designed as a combination of hardware and software to run Linux. Raspberry Pi OS is tightly integrated with the hardware and well supported, which will hopefully spare me the nightmares of Linux updates frequently breaking X-Windows back in the day.

Finally, I wanted a computer for experimenting with various computing technologies, such as ARM on the desktop. And, of course, I wanted an extra computer to play with Medley and other Lisp systems.

The Pi 400 is a member of the Raspberry family at the heart of countless electronics and IoT projects. But, since I'm not a hardware guy, I'll use it mostly as a desktop productivity and software development environment.

Reviews

I extensively researched the Pi 400 and a key theme of what I learned is performance.

The reviews describe and evaluate performance through a wide range of experiences that doesn't make it easy to figure what to expect. Perhaps because the specs place the device at a spot of the performance spectrum along the transition between realizing responsiveness is suboptimal, and not noticing anything unusual about the way the system reacts.

Therefore, given the affordable price, I accepted the small risk of disappointment and went with the Pi 400.

What I think the reviews don't highlight enough is that, even at the lower end of the performance spectrum, Raspberry absolutely nailed the combination of form factor and price of the Pi 400. It sits at a local maximum in the product space that delivers tremendous value for the money.

Hardware

The Italian keyboard of my Pi 400, which makes up the entire device, has nearly the same size as the TedGen keyboard of my Chromebox. The keys of the Pi 400 are actually slightly larger than those of the TedGen and support well my typing speed, which is not much.

I feel at ease with the Pi 400 keyboard because I prefer short-travel chicklet units. The plastic feel and feedback aren't an issue for me as, again, the mechanics and build don't interfere with my relatively slow typing.

Although not as smooth and precise as the Logitech mouse of my Chromebox, the Pi 400 one is acceptable despite the occasional lower than average responsiveness.

The Pi 400 instantly recognized the new Full HD webcam as well as my Mixcoder E9 Bluetooth headphones and Brother HL-L2340DW wireless printer. The webcam delivers a smooth feed with Google Meet and good image quality for the price.

Software

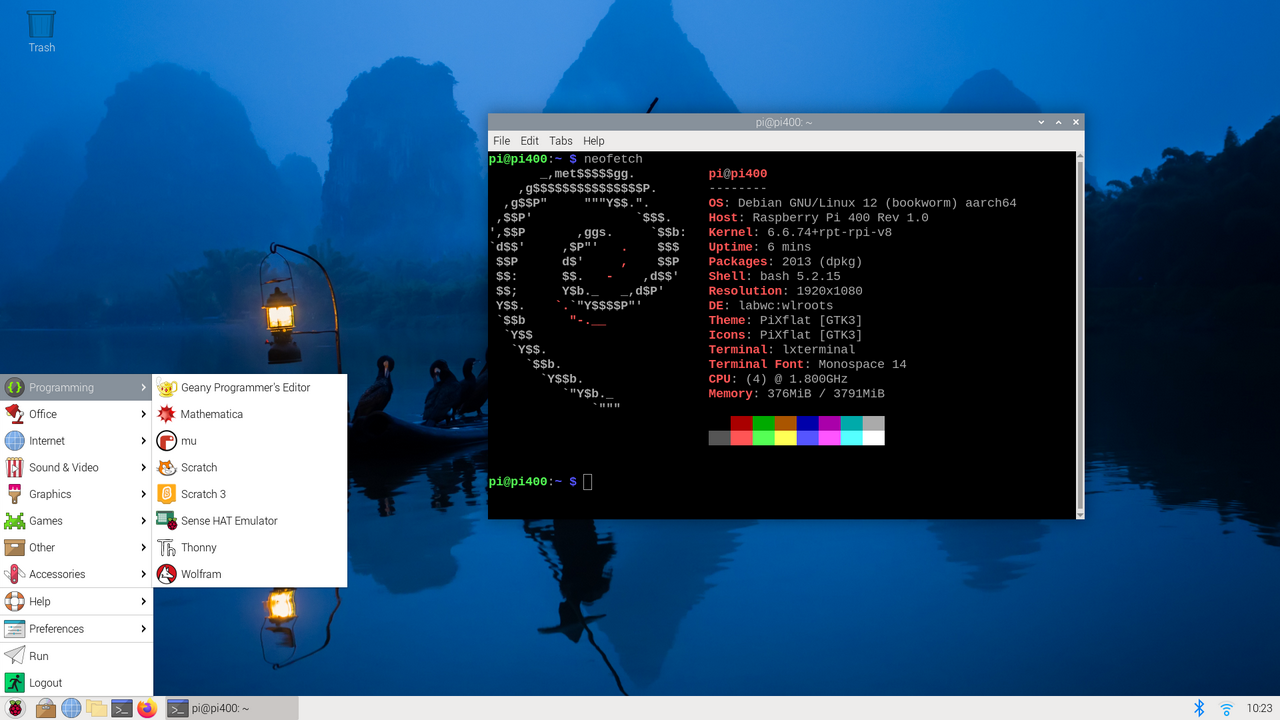

I've been using Unix since the early 1990s and Linux since the mid 1990s, so the Raspberry Pi OS desktop and system look mostly familiar.

I personalized the desktop environment to make it look similar to my Chromebox. I set a similar background color, moved the taskbar to the botton like the chromeOS shelf, and set Chromium as the default browser with a matching tab layout.

This is what my Raspberry Pi OS desktop looks like:

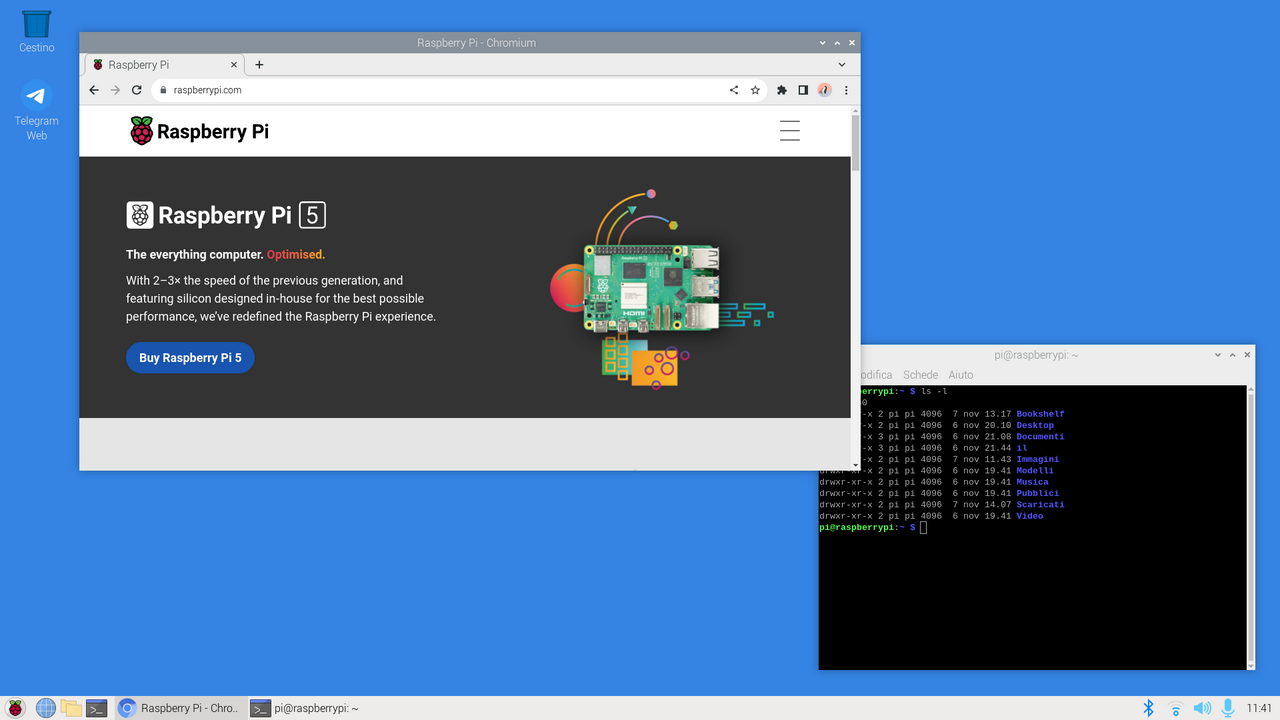

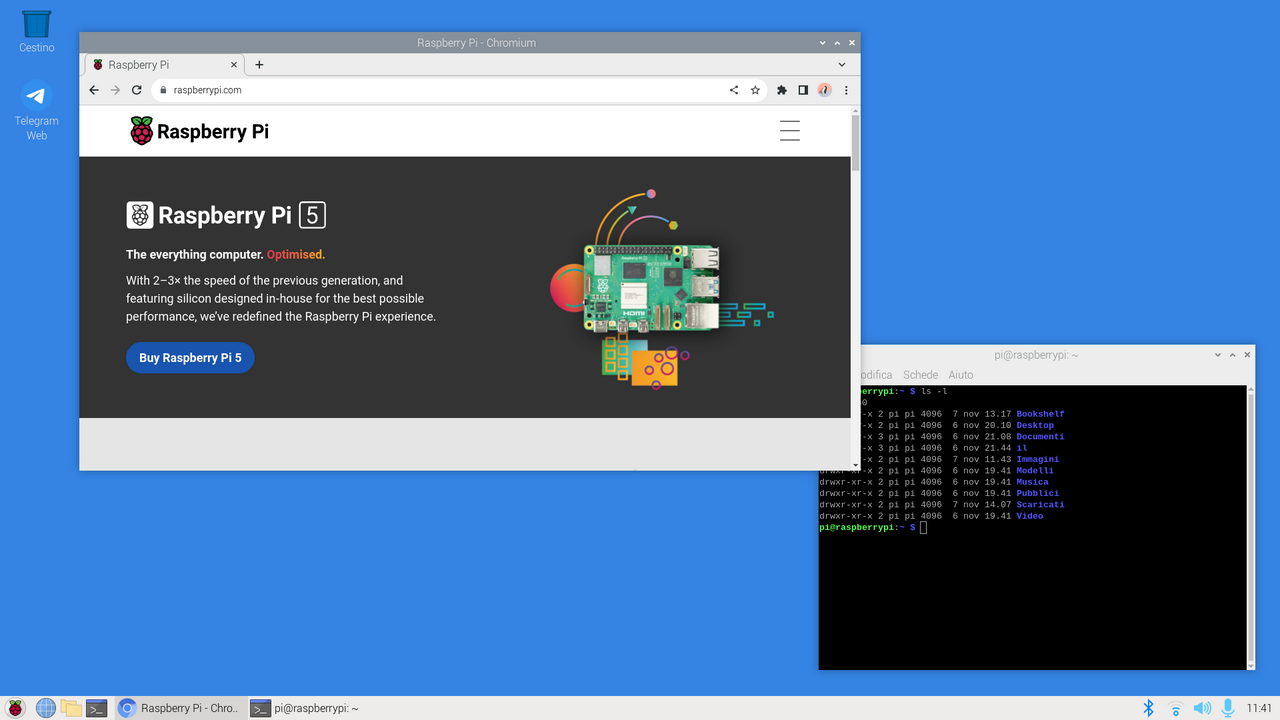

Since my daily driver on the desktop is a Chromebox I mostly live in the browser, with a number of tabs often open on Google products. On the Pi 400 Chromium works well enough with Google web apps. But I can't synchronize my extensions and settings with chromeOS as Google removed the functionality from Chromium.

Although most of the programs I need are available, I haven't found an easy to install screencasting tool with Wayland support.

Usage

I don't leave the Pi 400 permanently on the desk but set it up on demand.

Whenever I need the device I bring it out, set it on the desk, and connect the cables. One of the cables goes into the HP monitor which the Pi 400 shares with the Chromebox. I can use either computer by switching the monitor input signal with a button.

The only Ethernet wall socket close to the desk is permanently hooked to the Chromebox. The Pi 400 accesses the network over Wi-Fi at up to 70-80 Mbps.

Setup and configuration

To initially set up the Pi 400 I connected it to the Ethernet socket so the required large file downloads and system updates could go faster.

For installing the operating system on the microSD card I originally planned to run the Raspberry Pi Imager tool on my Chromebox under the Debian based Crostini Linux. But, although Raspberry Pi OS is derived from Debian, the only binaries of such an essential tool are available only for Ubuntu. Raspberry does provide instructions for building a package for Debian but network installation on the Pi 400 seemed simpler.

I selected the 64-bit version of Raspberry Pi OS Bookworm desktop and recommended software.

Despite the simplicity of the process, which can complete in less than a quarter of an hour, it took me three reinstallations and a couple of hours because of a subtle Raspberry Pi Imager bug.

I also configured SSH and headless access to the Pi 400 from my Chromebox with the recommended VNC client TigerVNC, the only one that supports Wayland on Raspberry Pi OS Bookworm. But the Pi 400 is just too slow and laggy over VNC with my setup, which makes it viable in a pinch.

The Pi 400 is no gaming rig but delivers enough performance for most ordinary tasks without the feel of constant wait and lag.

This supports well the kinds of tasks I ordinarily carry out such as running a browser with half a dozen tabs, a terminal, and another program or two. I don't consume much media.

The most noticeable manifestation of performance limitations is that programs don't start up instantaneously. For example, Chromium comes up in about 4 seconds. But once programs start, they run with mostly instantaneous responsiveness for common tasks.

YouTube streams consistently smoothly over Wi-Fi at 1080p and full screen, but entering or leaving full screen mode freezes the browser for a few seconds.

I don't mind the overall experience as I'm used to systems with similar architecture like cheap Android tablets and Chromebooks. The Pi 400 actually feels snappier than my Lenovo Yoga N26 Chromebook.

Although not architecturally similar to the Pi 400, the 8-bit single board computers I use for my retrocomputing projects, such as the Z80-MBC2, deliver a comparable feel that's part of the expected experience.

Speaking of retrocomputing, one the reason I got the Pi 400 is to run Medley, other historical Lisp systems, and emulated classic computers at a level of performance closer to the originals. Running Medley on powerful desktop systems or in the cloud is much faster, thus limiting the appreciation of certain design decisions, features, or workflows the systems imposed back in the day.

The more I use the Pi 400, the more the perception of not operating a powerful computer is fading away as I focus on the tasks I use it for.

An example can express and synthesize this perception. As I said earlier, I configured the desktop environment of the Pi 400 to look similar to that of my Chromebox. The Pi 400 often feels so smooth I forget I'm not on the Chromebox.

Conclusions

it's been a week since I unboxed the Pi 400 and I love it.

The product has the perfect combination of features, form factor, and price for my needs. This surprisingly capable little computer is one of the rare lovely products that encourage to use it, be productive, and have fun.

#pi400 #linux

Discuss...

Email | Reply @amoroso@oldbytes.space