An Interlisp file viewer in Common Lisp

I wrote ILsee, an Interlisp source file viewer. It is the first of the ILtools collection of tools for viewing and accessing Interlisp data.

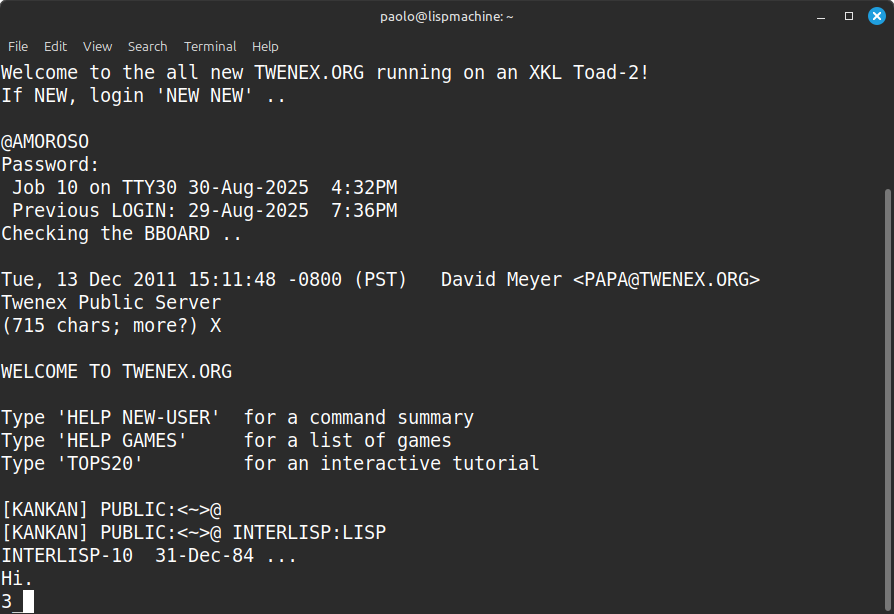

I developed ILsee in Common Lisp on Linux with SBCL and the McCLIM implementation of the CLIM GUI toolkit. SLY for Emacs completed my Lisp tooling and, as for infrastructure, ILtools is the first new project I host at Codeberg.

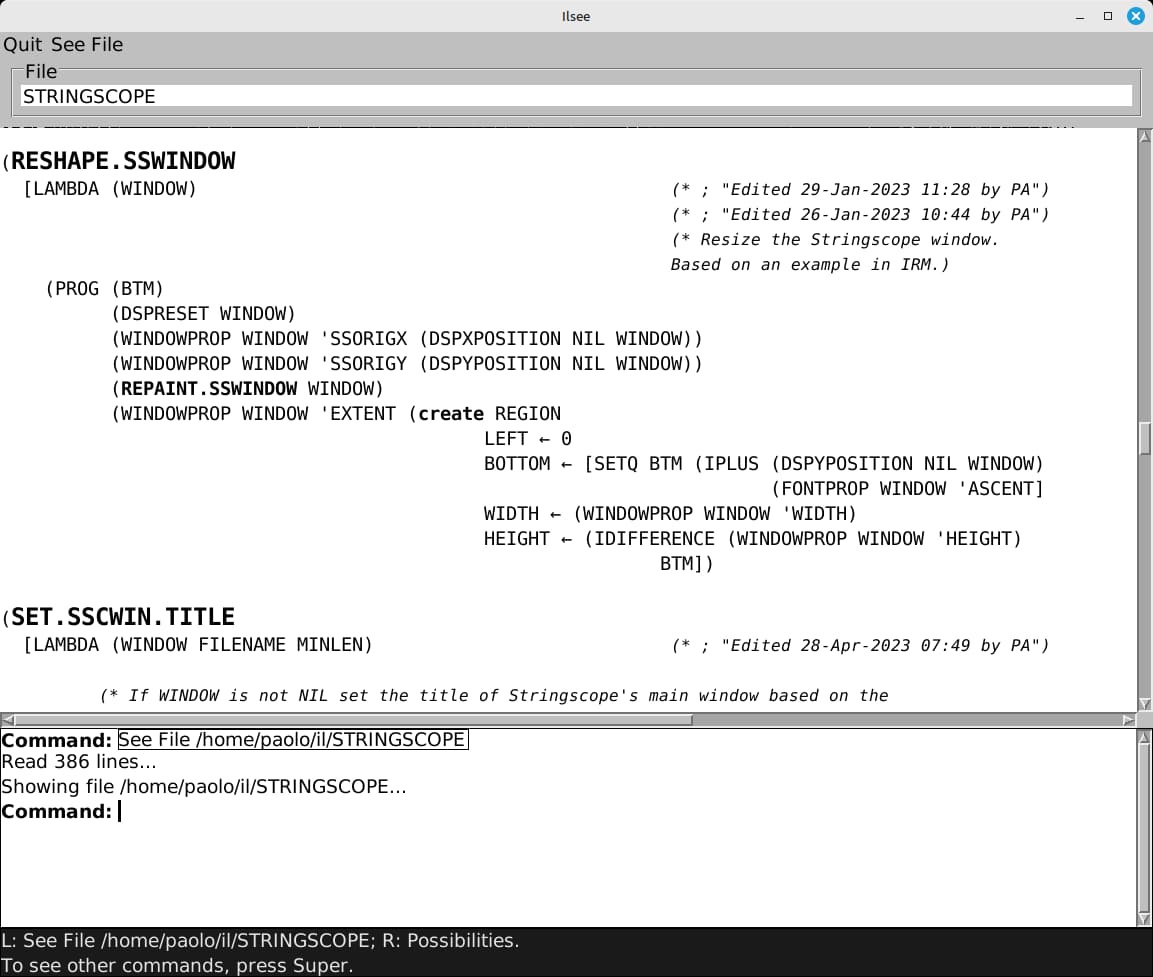

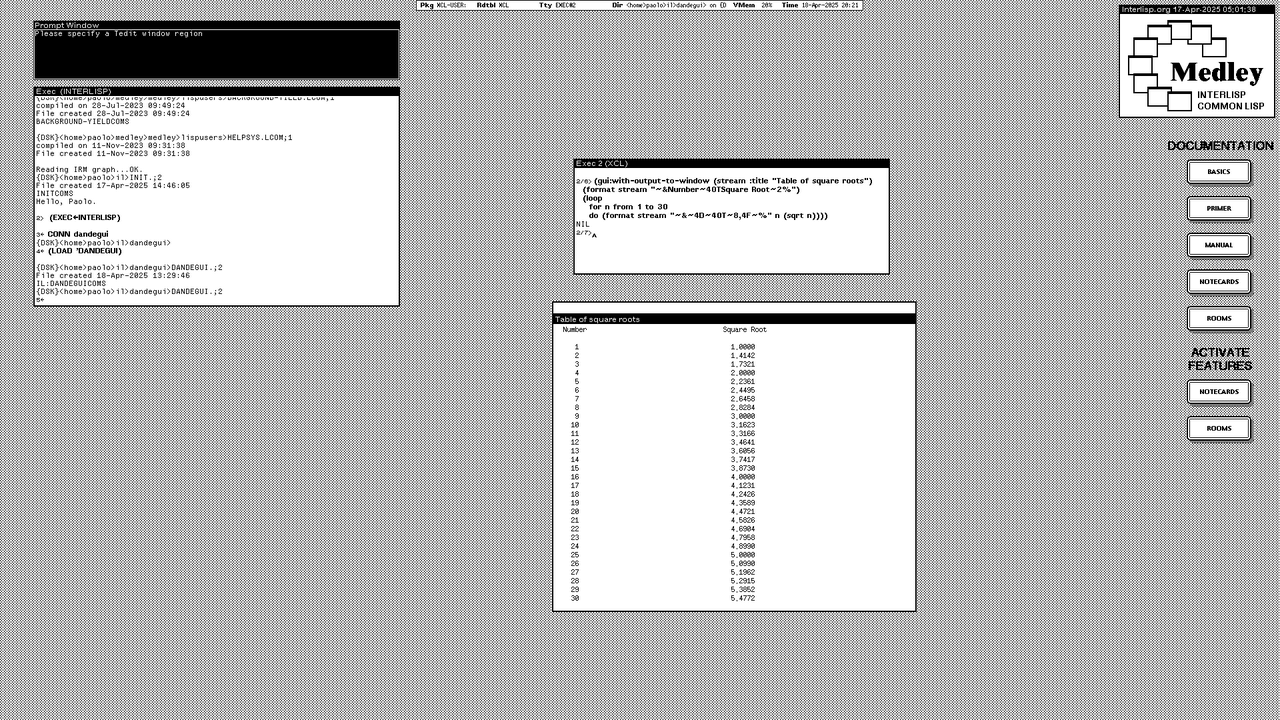

This is ILsee showing the code of an Interlisp file:

Motivation

The concepts and features of CLIM, such as stream-oriented I/O and presentation types, blend well with Lisp and feel natural to me. McCLIM has come a long way since I last used it a couple of decades ago and I have been meaning to play with it again for some time.

I wanted to do a McCLIM project related to Medley Interlisp, as well as try out SLY and Codeberg. A suite of tools for visualising and processing Interlisp data seemed the perfect fit.

The Interlisp file viewer ILsee is the first such tool.

Interlisp source files

Why an Interlisp file viewer instead of less or an editor?

In the managed residential environment of Medley Interlisp you don't edit text files of Lisp code. You edit the code in the running image and the system keeps track of and saves the code to “symbolic files”, i.e. databases that contain code and metadata.

Medley maintains symbolic files automatically and you aren't supposed to edit them. These databases have a textual format with control codes that change the text style.

When displaying the code of a symbolic file with, say, the SEdit structure editor, Medley interprets the control codes to perform syntax highlighting of the Lisp code. For example, the names of functions in definitions are in large bold text, some function names and symbols are in bold, and the system also performs a few character substitutions like rendering the underscore _ as the left arrow ← and the caret ^ as the up arrow ↑.

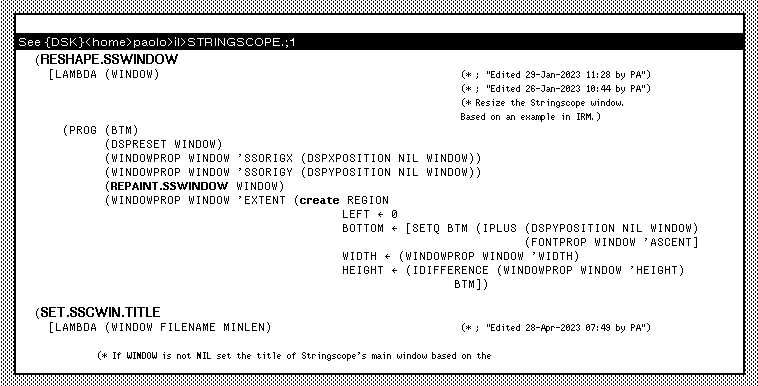

This is what the same Interlisp code of the above screenshot looks like in the TEdit WYSIWYG editor on Medley:

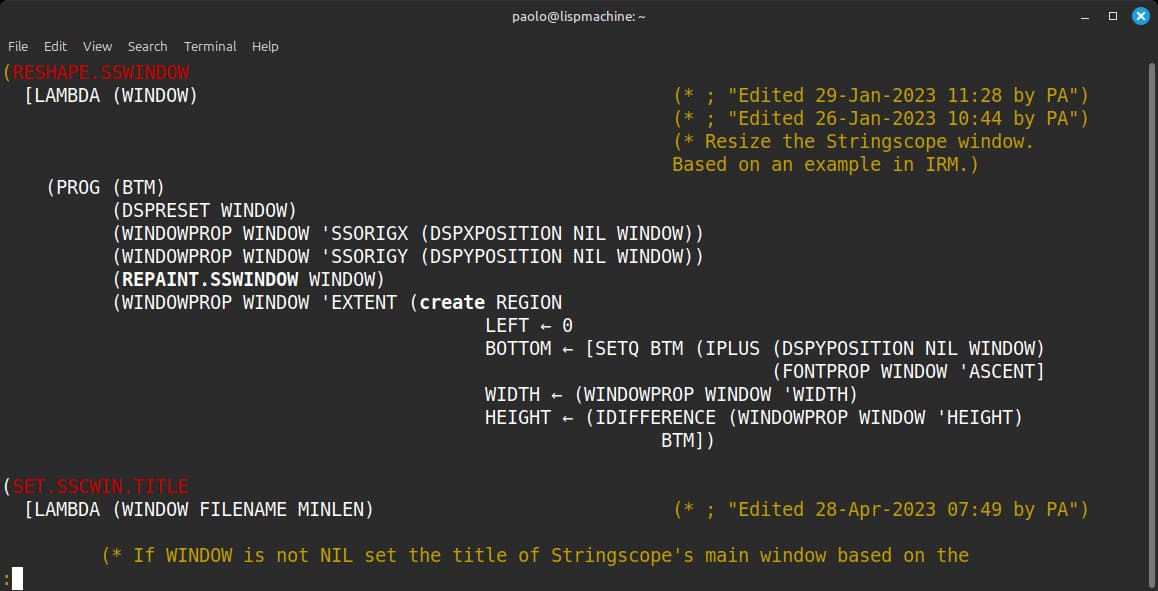

Medley comes with the shell script lsee, an Interlisp file viewer for Unix systems. The script interprets the control codes to appropriately render text styles as colors in a terminal. lsee shows the above code like this:

The file viewer

ILsee is like lsee but displays files in a GUI instead of a terminal.

The GUI comprises a main pane that displays the current Interlisp file, a label with the file name, a command line processor that executes commands (also available as items of the menu bar), and the standard CLIM pointer documentation pane.

There are two commands, See File to display an Interlisp file and Quit to terminate the program.

Since ILsee is a CLIM application it supports the usual facilities of the toolkit such as input completion and presentation types. This means that, in the command processor pane, the presentations of commands and file names become mouse sensitive in input contexts in which a command can be executed or a file name is requested as an argument.

The ILtools repository provides basic instructions for installing and using the application.

Application design and GUI

I initially used McCLIM a couple of decades ago but mostly left it after that and, when I picked it back up for ILtools, I was a bit rusty.

The McCLIM documentation, the CLIM specification, and the research literature are more than enough to get started and put together simple applications. The code of the many example programs of McCLIM help me fill in the details and understand features I'm not familiar with. Still, I would have appreciated the CLIM specification to provide more examples, the near lack of which makes the many concepts and features harder to grasp.

The design of ILsee mirrors the typical structure of CLIM programs such as the definitions of application frames and commands. The slots of the application frame hold application specific data: the name of the currently displayed file and a list of text lines read from the file.

The function display-file does most of the work and displays the code of a file in the application pane.

It processes the text lines one by one character by character, dispatching on the control codes to activate the relevant text attributes or perform character substitution. display-file does incremental redisplay to reduce flicker when repainting the pane, for example after it is scrolled or obscured.

The code has some minor and easy to isolate SBCL dependencies.

Next steps

I'm pleased at how ILsee turned out. The program serves as a useful tool and writing it was a good learning experience. I'm also pleased at CLIM and its nearly complete implementation McCLIM. It takes little CLIM code to provide a lot of advanced functionality.

But I have some more work to do and ideas for ILsee and ILtools. Aside from small fixes, a few additional features can make the program more practical and flexible.

The pane layout may need tweaking to better adapt to different window sizes and shapes. Typing file names becomes tedious quickly, so I may add a simple browser pane with a list of clickable files and directories to display the code or navigate the file system.

And, of course, I will write more tools for the ILtools collection.

#ILtools #CommonLisp #Interlisp #Lisp

Discuss... Email | Reply @amoroso@oldbytes.space